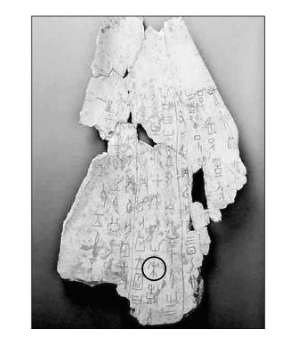

The character “wheat” in oracle bone inscriptions (circled area).

- Agricultural production climate and cultivation techniques

From the perspective of agricultural production climate, wheat originated in West Asia and belongs to the Mediterranean climate. The main rainy season is in winter and spring. It is a summer-harvested crop sown in winter and harvested in summer. Spring is the growth period and it needs water the most. However, the East Asian region where China is located belongs to a monsoon climate. The main precipitation is concentrated in summer. In spring, there is generally a lack of rain. There is a saying that “spring rain is as precious as oil”. This situation is very unfavorable for the jointing and filling of wheat during its growth period. And the frequent rainfall in summer affects the ripening and harvesting of wheat.

Therefore, in order to plant wheat on a large scale, ancient Chinese ancestors had to solve the irrigation problem first. Only when the irrigation system reached a certain level could wheat be planted on a large scale. Therefore, although wheat had been widely planted since the Shang and Zhou dynasties, it still did not replace millet as the main crop in northern China until the Han Dynasty.

During the Ming and Qing dynasties, the widespread planting of wheat promoted the development of well irrigation technology. At that time, the spread and popularization of well irrigation technology in northern China was also evidence of the further expansion of wheat. In “Records of What I Saw and Heard in Jifu” by Huang Kerun during the Qianlong period, it was recorded that farmers in the Jifu area at that time: “Those near the river rely on the river. Those without a river dig wells. Then, except for barren land, there is no place where wheat cannot be grown, and there is no farmer who does not want to grow wheat.”

Sowing of dryland crops such as wheat.

From the perspective of cultivation techniques, wheat entered the Central Plains from the northwest of China. Its initial cultivation season and method were the same as that of millet, sown in spring and harvested in autumn, borrowing the cultivation techniques of millet. This is exactly the “spring wheat” mentioned in “Qimin Yaoshu by Jia Sixie” that is “sown in March and ripened in August”.

After wheat was introduced, it initially followed the cultivation techniques of millet, sown in spring and harvested in autumn. Later, it was changed to be sown in the previous autumn and harvested in the next summer. With this change, wheat truly began to adapt to the oriental land and water, and thus had an important technical foundation for spreading to a wider range.

- Traditional eating habits and food processing technologies

When wheat was first introduced to China, ancient ancestors actually didn’t know how to eat wheat. This sounds ridiculous, but it is indeed a fact. Many ancient Chinese documents record that wheat was an “inferior” grain. For example, Yan Shigu’s “Jijiu Pian” says, “Meals of wheat and soups of beans are only food for peasants and wild people.” Translated into modern language, it means that meals steamed with wheat and soups cooked with soybeans are only for the poor. So what did the upper-class people eat at that time? They ate meals steamed with millet or rice.

Why did the ancients belittle wheat like this? That’s because the ancient Chinese eating habit was the tradition of eating whole grains. Whether it was rice in the south or millet in the north, they were all cooked or steamed whole. This tradition of eating whole grains is not only reflected in the processing of grains but also in food cooking methods and corresponding cooking utensils and tableware.

Wheat must be ground into flour before it can be processed into various foods. If wheat grains are steamed or boiled whole, it is not only difficult to digest but also has a very poor taste and is hard to swallow. Therefore, there is another issue that cannot be ignored for wheat to take root and develop in China, that is, the evolution of food processing tools and technologies. Without the support of suitable processing tools and eating technologies, delicious wheat food products cannot be obtained, and wheat will not attract the interest of a wider range of people.

In the early days of history, grains were roasted on stone slabs. Thanks to the progressive improvement of ancient cooking utensils (The evolution history of cooking utensils), the cooking tradition of steaming and boiling was established, and the cooking and eating methods of “steaming grains into meals and boiling grains into soups” were gradually invented, which is also a witness to the ancient tradition of eating whole grains. For a long time after wheat was introduced, its consumption borrowed the existing tradition of eating whole grains. But obviously, the taste of eating wheat grains is far inferior to that of rice and millet. This not only affected its spreading speed but also affected the manifestation of its edible value.

Stone mills and pestles in the Neolithic Age.

Later, with the evolution of grain processing tools and methods such as pestles, mills, and grindstones (From “whole grains” to “flour-based foods”, grain processing has undergone these evolutions), ancient ancestors began to grind wheat grains into crushed grains (called “half-grain eating”) and then steam and eat them. Then, through processing tools such as stone mills, wheat was crushed and ground into flour, gradually transitioning to the stage of refined pasta. The birth of the mill is considered an important factor in making wheat pasta popular and promoted. It not only changed people’s traditional way of eating soybeans and wheat grains but also promoted the large-scale promotion and cultivation of wheat.

Pottery figurines making pasta, unearthed from Tomb No. 201 in Astana, Xinjiang.

Video source: Chinese Poetry Conference.

At the beginning, there was not much attention paid to the names of pasta. Naming them after their shapes and production methods was the most direct choice. Just as Wang Sanpin of the Ming Dynasty quoted “Miscellaneous Records” in “Research on Ancient and Modern Things” and said, “All foods made with flour are called cakes. Therefore, those baked with fire are called sesame seed cakes. Those cooked in boiling water are called pulled noodle cakes. Those steamed in a steamer are called steamed cakes.”

Different from the Western tradition of baking bread, the “Oriental steamed cake” steamed bun is the successful application of the traditional steaming method for thousands of years on pasta. It is a representative of China’s steaming food tradition and also an important difference between Chinese and Western food cultures.

Gradually, pasta became a new food habit in ancient times. The influence of this food habit on the localization of wheat has transformed the original “resistance” into “driving force”.