I. The Past and Present of Chinese Lanterns

Zigong Lantern Festival in Sichuan

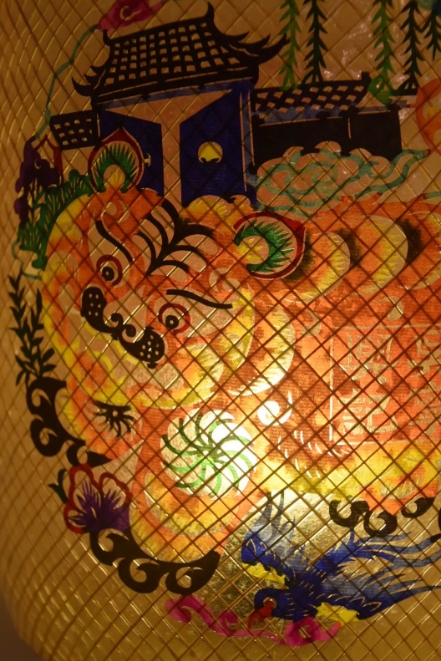

Bamboo Silk Lanterns in Dongyang, Zhejiang. Ancient Buildings

Bamboo Silk Lanterns in Dongyang, Zhejiang. Ancient Buildings. Photographed by bot

II. Varieties of Chinese Lantern Art

Lanterns in Dongyang, Zhejiang

Bamboo Weaving Lanterns in Chaozhou

Dong Tianbu’s Son-in-law Lantern in Kinmen area

Dong Tianbu’s Son-in-law Lantern in Kinmen area

Fengxian Rolling Lantern

Wangmantian Fish Lantern in Shexian County, Anhui Province

Suzhou Night Market

Lanterns in western Fujian

Qinhuai Lantern Festival

Boneless Lantern in Potan, Xianju, Zhejiang

III. Several unique colored lanterns in China.

01 Horse Lantern

Horse Lantern

02 Guan Gong Knife Lantern

Guan Gong Knife Lantern

Dragon Lantern at Li Family’s Dragon Palace Square

Hexagonal Palace Lantern of Dragon Palace

Painted Lantern on the Eaves of Li Family’s Dragon Palace

Gauze Lantern

Gauze Lantern